This article originally appeared in the Smithsonian's Folklife Magazine, as part of the series "A Stream of Voices" co-presented by the Endangered Languages Project and the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

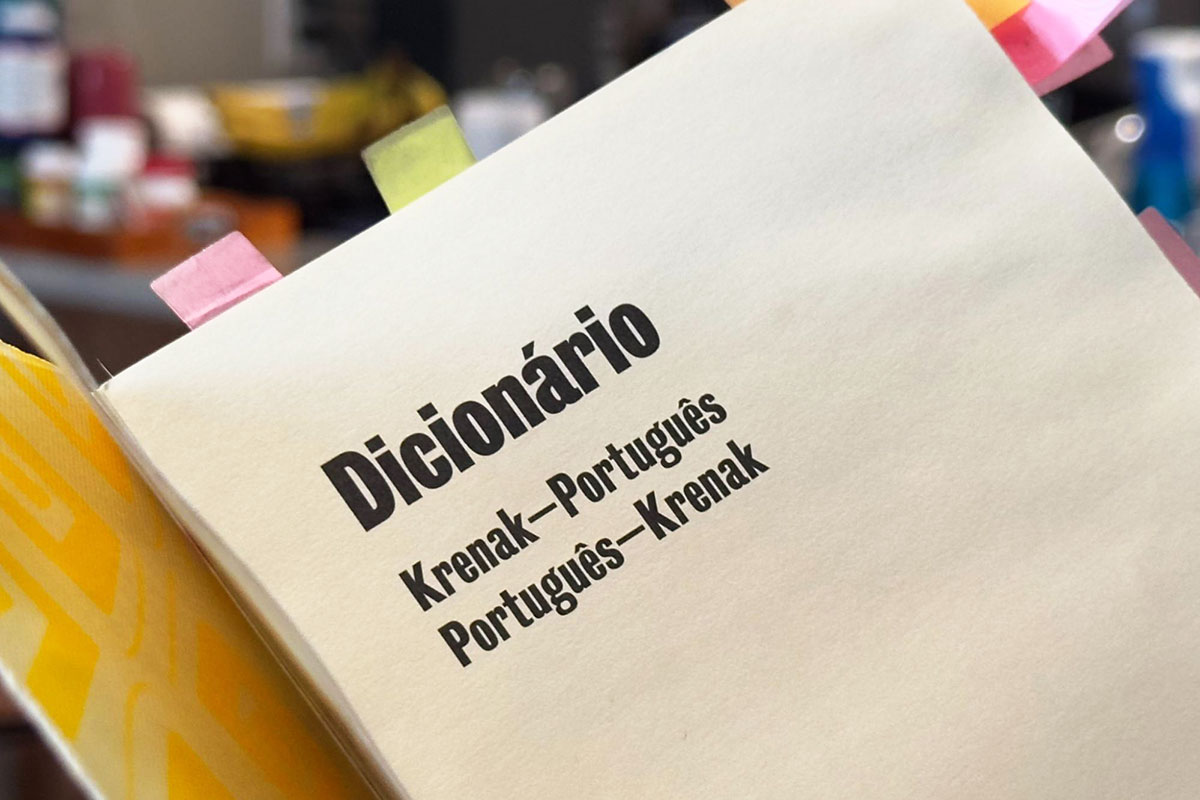

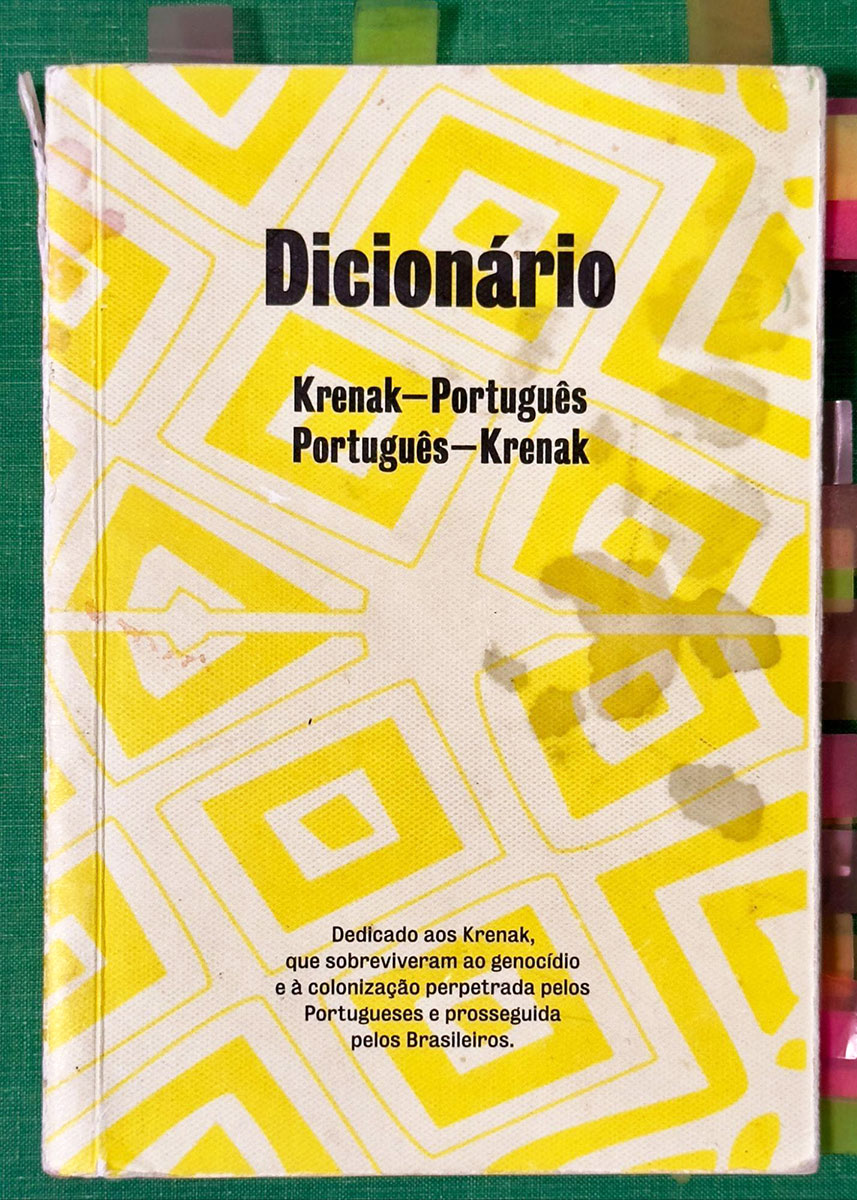

I was eight years old when my family was gifted a copy of the Krenak dictionary. Published in 1909 and collected by Bruno Rudolph, a German settler in Eastern Minas Gerais, Brazil, only about a hundred copies of the bilingual Krenak-Portuguese dictionary had been printed, and it was an honor to receive one.

It was 2010, and I vividly remember how, through the following months and years, both my parents would evoke the little yellow book as a source of knowledge and culture. The dictionary was the thing we would turn to for questions and inquiries about our Krenak heritage, our ancestral language (of the Jê language family), and history. Living above the fireplace of our home in Viamão, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil—about 1,300 miles from the modern-day, federally demarcated Krenak territory in Minas Gerais—the book was a bridge between my two worlds.

Throughout my mom’s deep dives in the dictionary—which served as the primary source for her doctoral research on Krenak mathematical practices—my sister and I would often be met with full-blown Krenak sentences when walking into her home office. Even as the non-Indigenous parent, my mom always made a point to expose me and my siblings to our Krenak heritage. She wanted us to wear our Indigeneity with pride, and making space for the language in our lives was her way of helping. As a kid, hearing my full-time student mom so frequently talk about Krenak numbers ensured I would never forget how to count in the language.

Some dictionary entries, like gran jipakischu te minjan jop, “the great snake drinking water,” or simply “rainbow,” sparked such a curiosity inside us that we would have fun for days trying to guess the contexts in which Bruno—the German author, essentially a first-name-basis friend in our household—came across them. Others, like mawon, “mixed-race,” became part of our vocabularies, useful when introducing ourselves as distant children of the Krenak people. For the next week or month, one of us three—my guiupu (mom), Mi’am (my sister), or I—would find an opportunity to use these newly learned words, evoking memories not only from our time studying them together from the dictionary but also from Bruno’s history, which we all felt connected to in some way.

Perhaps due to my family’s active interest in language vitality projects within our home community, I ended up pursuing a linguistics degree in college. I saw a lot of my own language-reclamation journey reflected in my studies. The same fun words I learned at home now occupy my computer’s storage, transcribed into multiple spreadsheets and databases I use for research. My senior honors thesis project mainly focused on uncovering and contextualizing past traditional ecological knowledge from centuries-old linguistic records and materials, such as Bruno’s Krenak dictionary.

In linguistics, we often refer to these resources as “legacy materials.” They are secondhand linguistic data, acquired from past documentary efforts, mainly undertaken by outside scholars and/or missionaries. To the untrained eye, these materials might look incomplete, inaccurate, or incorrectly collected. But that’s if we’re judging them by today’s standards. Their authors were collecting wordlists and sketching grammars decades before the field of language documentation had been formally established within linguistics. Judging their work by today’s standards, these materials would be considered anachronistic, overlooking the historical context in which they were created.

Further complicating the reliability of legacy materials is the fact that many of their authors documented languages only incidentally, often as a secondary task to their primary occupation. In a 1990 paper that draws a bibliography for the study of Krenak, Lucy Seki—the late Brazilian linguist and pioneer in the study of Jê languages—acknowledged this to be an issue for most of our country’s Indigenous languages, not only Krenak: “[the] language was only considered a means of achieving non-linguistic goals, related to the [author’s] primary occupation” (my own translation from Seki’s Apontamentos para a bibliografia da língua Botocudo/Borum).

This is particularly true of Bruno’s dictionary. As a botanist trained at the University of Leipzig, he worked as a pharmacist for railroad workers during the construction of the Bahia-Minas train line—which connects Brazil’s mineral-rich state of Minas Gerais to coastal Bahia, where exports are taken out of the country—a project deeply tied to the state of environmental damage the Krenak live through today. With this context in mind, it’s crucial to acknowledge that Bruno’s work, while valuable, is intertwined with the expansion of colonial powers through our territories, which has immensely contributed to the endangerment of our culture, language, and ecological knowledge.

As a result of his primary interest in plants and nature, especially as they related to medicine and health, a large percentage of the dictionary entries belong to the environmental domain. Snake, plant, and bird names account for approximately 500 of the total 3,290 entries, often accompanied by Bruno’s comments on the word’s structure or the context in which he documented it.

In my current research, I aspire to reconstruct twentieth-century Krenak ecological knowledge by analyzing and contextualizing Bruno’s ideas within our cultural system, drawing comparisons to the practices of stewardship and care for the land found in our communities today. Currently, most Krenak adults are monolingual Portuguese speakers. Due to the history of mineral exploitation, land invasion, and forced displacement, I fear that not only has the environment dramatically changed but so have the ways we interact with it as a community. In a way, though still apprehensive of its origins and implications, I now feel lucky to be working with a historical document so rich in fauna and flora content. It aids the analysis of past Krenak ecologies and connects me and other language learners to our ancestors’ millennia-old wisdom.

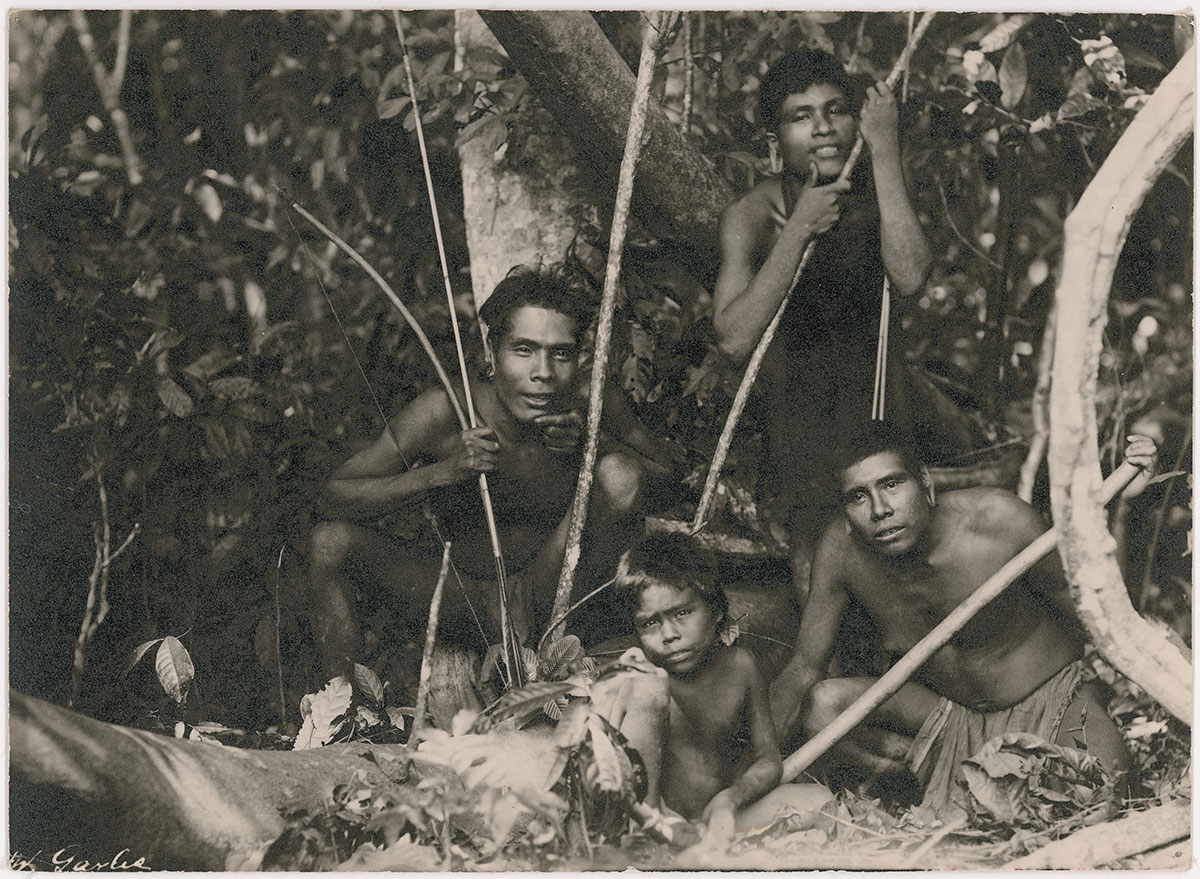

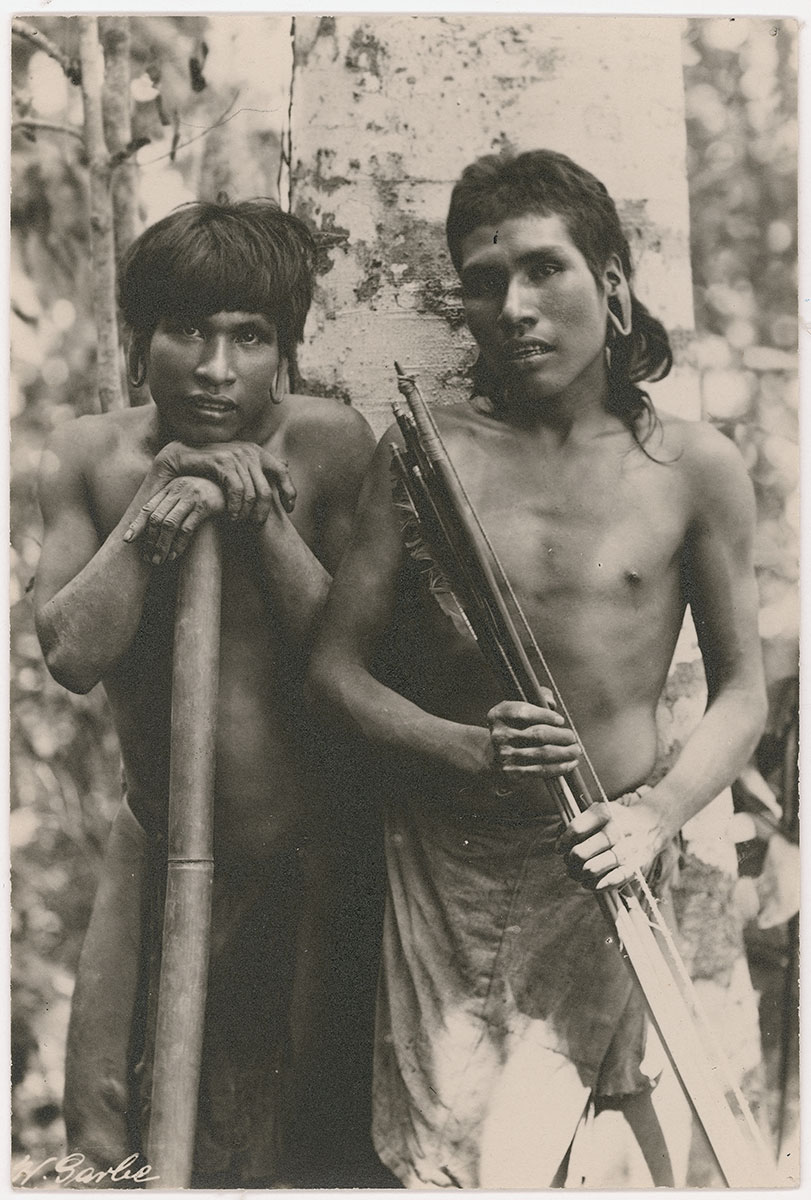

As for accuracy, the 1909 dictionary has been widely debated, both within academic and Krenak communities, who since 2010 have attempted to use it as a language-learning tool. As a traditionally nomadic community, the Krenak have traveled up and down the Watu river—renamed Rio Doce by the Portuguese settler-colonial population—for generations, settling in areas between Southeastern Minas Gerais and the Atlantic Ocean, and thus forming distinct subgroups. Due to their different histories of contact and language development, these smaller groups spoke distinct dialects of Itchok, “the language,” which were often recorded by settlers and explorers without proper regard for language variation or respect for the communities who spoke them.

During the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–1985), the federal government’s land-grabbing policies, driven by the expansionist agendas of local farming oligarchies, made the Krenak particularly vulnerable. These policies violently uprooted our ancestors to forced-labor farms and correctional facilities, where they lived alongside Indigenous peoples displaced from across Brazil. This involuntary contact—a source of intergenerational trauma within some Krenak families—likely contributed to even more drastic variations in the language and disrupted the cultural continuity of our communities, especially as some of our displaced ancestors chose not to return to the Watu after being freed.

As a result, today, the second-largest Krenak community can be found in the state of São Paulo, on the Vanuíre Indigenous Land, a federally recognized territory shared with Kaingang, Terena, Guarani, Atikum, Fulni-ô, and Pankararu parentes (“relatives,” a term of endearment used by Brazilian Indigenous peoples with each other).

Centuries of ecological degradation on our already dispersed communities have turned holding onto our language a long-standing challenge, where talking about the environment in the Itchok is not only rare but also an act of resistance. As the great-grandson of the Krenak who chose to settle in Governador Valadares—a medium-sized city in the vicinity of the Minas Gerais Krenak territory—I suspect the actual speech of my ancestors to have been quite different from the language taught today in the local, community-run school.

Another way this interplay of geographic dispersion and linguistic variation can be seen is through a basic review of the distinct Krenak word lists collected in the past two centuries. We know Bruno, whose dictionary is the largest Itchok collection, was in the Watu valley, so we can trace what Krenak groups he likely contacted. But other authors of Krenak records—like German prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied and Canadian linguist Charles Frederick Hartt—were much farther north in the state, documenting the speech of Krenak groups who resided closer to the state border with Bahia. While there are certainly Eurocentric biases embedded in these records—stemming from the authors’ limited understanding of linguistically diverse communities—some of what might initially appear as inaccuracies in transcription could be understood as genuine dialectal variations or even accents.

Other issues relating to legacy materials stem not only from their collection but also their afterlives. Many, like Bruno’s dictionary, were taken back to the author’s homelands. The Krenak dictionary was originally printed in 1909 Germany by F.W. Thaden, an academic publisher based in Hamburg, storing the language an ocean away from its original keepers. Only in 2010 was it translated and republished in Portugal, in a partnership between the Lisbon-based Maumaus visual arts school and the Krenak community of Minas Gerais. The century in between, however, marked the steepest decline in Itchok use, when language documentation could have been the most useful.

As linguists Saul Schwartz and Lise Dobrin explain in a 2021 paper, this is true for many legacy materials, which are stored away in archives or private collections or often embedded in published literature. For the two scholars, legacy materials are key to language revitalization and research, especially in cases where they offer the most exhaustive record of the language—as is the case with Krenak. Curiously, thirty-one years earlier, Seki had expressed the same idea when discussing Krenak language materials, noting that past linguistic documents constitute the sole source for studying historical changes in the language, including its variety spoken today. For me, this alignment is noteworthy because it shows how concerns about the preservation and usefulness of legacy materials have endured over decades, becoming central to the limited scholarship there is on our Itchok.

Knowing all the limitations and issues of working with legacy materials, I still struggle to wrap my mind around all their potential. While these documents may be the most useful resources in revitalizing almost or completely lost languages, it’s important to remember that they aren’t ready-to-go learning tools. Not many people are learning to speak our Itchok from reading it off a word list. Bruno didn’t compile the dictionary with future Krenak generations in mind, or how they may use his manuscript to reclaim the now severely endangered tongue. In legacy documentation, breathing life back into our languages has rarely been the authors’ intent, especially in the cases of European men who, during the peak of the Portuguese colonial project, traveled through, settled, and aided the exploitation of our unceded lands.

In recent decades, there have been impressive language revitalization initiatives based on legacy materials. From Native North America to Eastern Europe and West Asia, centuries-old documents have been reclaimed as part of the solution. The process of turning them into proper language-learning resources will always look different, depending on the nature of its collection and the outcome desired by the community. For some, legacy materials have provided insight into what the language used to look and sound like, a starting point from which linguists and language learners can then attempt to grammatically reconstruct speech. This is an elaborate and rather difficult process, often done by comparing how the language has developed and changed over time in comparison to closely related languages, like those from the same language family and/or geographical region. In other cases, legacy materials like Bruno’s—to this day, one of the few widespread Krenak written texts—can provide the community with a somewhat standardized writing system.

Bruno was consistent in his phonetic representation of the language throughout the dictionary, spelling words in a manner that Portuguese speakers could understand. The way he chose to write became the orthography of choice for some community members. As most people still do not read or write in Krenak, I would like to see a community-led effort to develop a writing system that best reflects our worldviews and relationship to the Itchok. But, for now, it’s nice to have a standard for writing that can be taught in the classroom, written on the blackboard, used by little kids on their homework, texted over WhatsApp, and passed down to younger generations.

While engaging legacy materials in endangered language education is a process that involves a seemingly formal process—digitizing, archiving, analyzing, comparing, reconstructing, bringing back—the actual decision-making process should always be led by individual language communities. Some materials are too culturally sensitive to ever resurface as useful learning tools, and others might be held onto by community members who feel it shouldn’t be shared with larger audiences. These are all appropriate responses to the colonial nature of these documents, and respecting the community’s wishes should always be a priority. But, if the legacy materials are to resurface and be reclaimed, I am interested in finding solutions that allow for its usability and access.

Although the process is exhausting, I remain hopeful for the myriad possibilities posed by legacy materials. Could they be adapted into textbooks? Could they be complemented by audiovisual recordings? Could they be shared online to reach community members in the diaspora? And, while I lack answers to these questions, as a learner, I continue to ground my language journey in the feelings I’ve grown to nurture for Bruno’s dictionary. Through so many in-depth readings over the years, I learned to treat the little yellow book as a relative, forming a bond of kin with the text, my ancestors, and Bruno.

It was during the COVID lockdown that I realized Bruno and his dictionary had really become parts of my family. I was finishing high school abroad in Canada when the world shut down. I was sent home to Brazil, and, in between Zoom classes and many failed attempts to bake cookies, I decided to reacquaint myself with the book. I hadn’t touched it since I left my parents’ home almost two years before. Partially inspired by “Native Twitter”—the algorithm-based wing of the app X, where Indigenous peoples congregate—I decided to do my own “word-of-the-day challenge.” Every morning, I would pour myself a cup of coffee and sit by the balcony, letting Tepó (the sun) shine on the pages that flipped through my fingers. As randomly as possible, I would land my right index at a word and, for the rest of the day, try to use it as many times as I could.

Whenever it came up, I would think back to Bruno and feel grateful for having access to it—this little yellow hardcover book, which managed to connect me with all the knowledge and lived experiences of my ancestors. Like many of my actual uncles and aunties, Bruno was and continues to be a source of wisdom, someone I turn to for advice. More than his book, Bruno has become kin.

About the author

Born in Governador Valadares to a mixed Krenak and Lebanese family, Antônio Jorge Medeiros Batista Silva is a former intern with the Endangered Languages Project and the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a graduate of Dartmouth College. His research interests include Indigenous languages, traditional knowledge, and archives.

About the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

The Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage is a research and educational unit of the Smithsonian that promotes greater understanding and sustainability of cultural heritage across the United States and around the world through research, education, and community engagement. It produces the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, exhibitions, symposia, publications, and educational materials. It also maintains the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections and manages cultural heritage initiatives around the world.