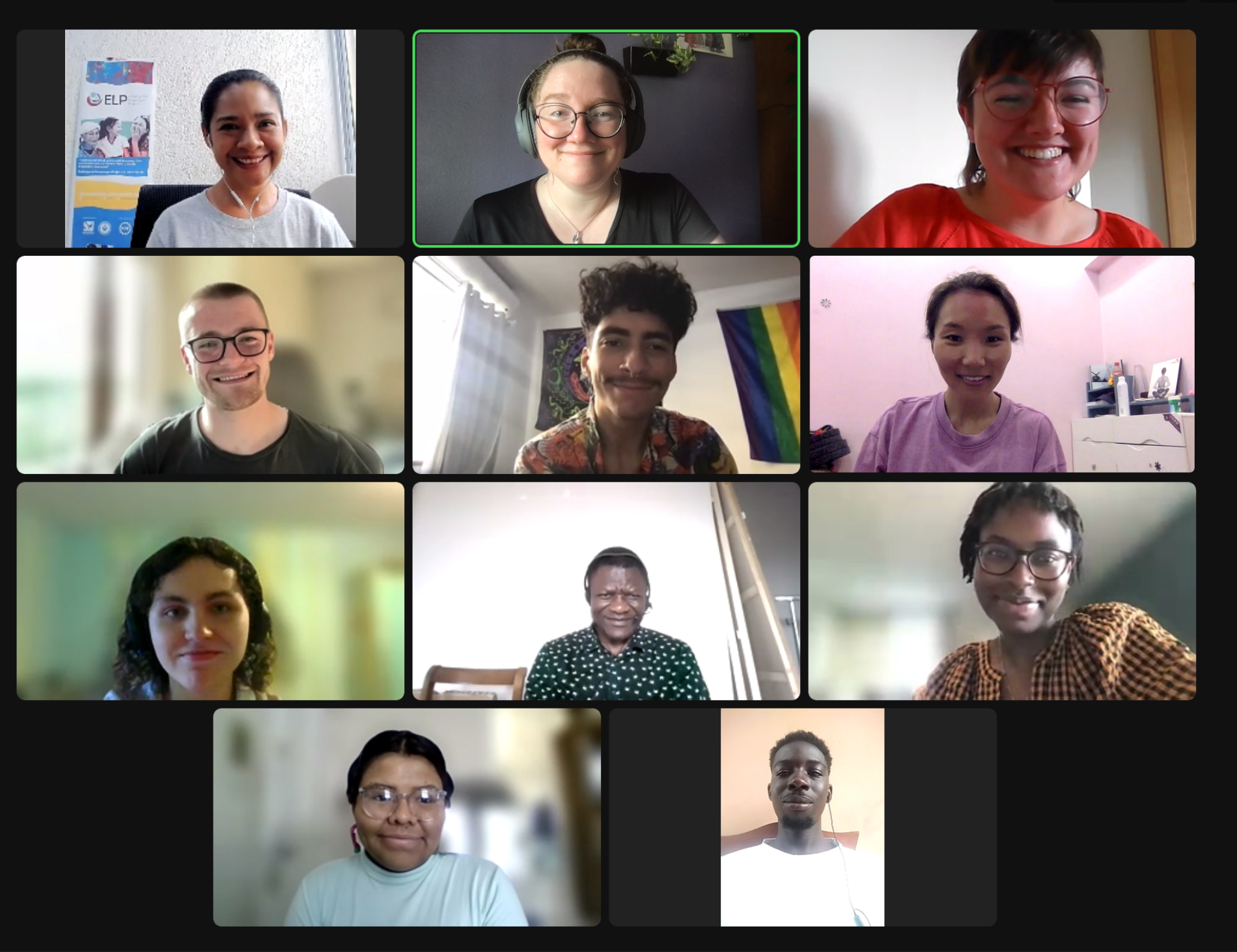

Last week, in a conversation with the ELP Language Revitalisation mentors and some of my fellow interns here at ELP, I had the privilege of learning from their first-hand experiences in language documentation and reclamation. I walked into this meeting — our first introduction to the ELP mentors — knowing that there was a lot to learn, but I did not expect to relate so deeply to each of their individual stories. More specifically, considering my own work with the Krenak language, my heritage tongue I've been a lifelong learner of, it amazed me that language champions from such diverse backgrounds could speak so concisely and precisely to my own struggles.

And, honestly, this is the beauty of ELP's proposal: the project's aim is to exactly build community in the trenches of language work.

For context, I am an undergraduate student in Linguistics and Native American & Indigenous Studies. Every summer, when I have the time to go home, I give it yet another shot in learning as much Krenak as I possibly can absorb in my 3-months-long break. This time, it was different. I got home with a grant from my university to work with my community and find gaps we could fill in the teaching of our language. We were brainstorming textbooks, illustrated children's comics, language nests… everything a linguist-in-training could think of. However, was that what the community most needed? Were any of my offerings in fact useful for their day-to-day reality?

There is one state school in the Krenak territory, where the Brazilian curriculum is taught along with the Borum Itchok — the Krenak tongue. One of the first objections my teammates and I were met with when talking to other community members was the idea that, although a beautiful dream, to draw an academic plan to raise L1 Krenak speakers was too utopian. Kids were already being schooled in Portuguese for decades now — and, even if involuntarily, we could not dismiss the colonial tongue for the doors it opens, both into formal education and into the job market.

Listening to this, not only did I quake in my proposals as a linguist, but also as a dreamer of Indigenous futurisms. After all, it was a dream of mine to create the conditions for generations of native speakers to rise. But, in reality, taking in the critique is immeasurably more valuable. From the position of an outsider — although a Krenak man, still a linguist trained abroad — it is key to take any and every feedback from the community seriously. It took me a bit of time to learn how to see these comments not as objections, but rather as constructive criticisms.

When the idea of a Krenak textbook was dismissed (for the printing costs and inaccessibility to materials), we were quick in finding ways around it. What surprised me, if I'm being honest, was the preference given to virtual resources. According to the elders we work with, dictionaries and textbooks aren't new. Many scholars, mostly European and North American, or settler-descendent Brazilians, have drawn from the Krenak language and people to come up with language resources. All of these are published, either as loose vocabularies or Masters/PhD dissertations. Not all of these are available to the public and, more importantly, to the community these scholars based their work on. Thus, our first solution was not to create new materials, but to reclaim the existing ones, turn them into video tutorials on Krenak sound systems, sentence formation, grammar, and more. Once we understood what the community really wanted, and stood down from the (often invisible to their own eye) pedestal scholars put themselves on, our work finally got a flow to it.

My project with Krenak is ongoing, and we're definitely far from reaching a conclusion to "how can we revitalise our language?" — and, perhaps, it'd be counterproductive if we had already. But what brings me inner peace is exactly the collective construction of our shared future as a language community. This isn't my bachelor thesis I'm working on — it is a once in a lifetime opportunity to be there for my relatives, ancestors, and the future generations of Krenak speakers.

In our conversation yesterday, it was brought up by Yazmín Novelo — one of our mentors, with whom you can schedule a free appointment! — that "there is no language work without social work" and, in my opinion, the same is true the other way around. To care for the Itchok (our language) is to care for the Borum (our people), and vice-versa. There cannot be any efforts to document our language without active participation of our people.

As someone who navigates both worlds, it is not always clear what my role is — I can't be the object of study, nor the one doing the study, so I better be the bridge.